By Brian Buchanan and Sue Harrington

One of the key aspects of our project is investigating regional differences in the burial evidence from AD c. 300-800 by comparing sites and monuments data recorded at Historic Environment Record (HER) offices and through investigating published and unpublished site reports. We have spent most of our time up to this point building our database of sites; with Sue focusing on a bespoke Access database detailing every individual grave in Northumbria based on archival research while Brian has built the GIS geodatabase of funerary sites and their spatial locations. As we are building distinct databases that will later be merged for analysis, we have encountered different problems with the types of data we are gathering and thought it would make an interesting post to look at some of the challenges we are encountering.

HER Data

Thus far we have obtained sites and monuments data from almost all of the English HERs in our study region, and are actively acquiring the remaining English data now (Figure 1). The next step in data collection is contacting the Scottish HERs over the next few months in order to build up our GIS database of sites. Many thanks are necessary to these HERs for their assistance in not only supplying the data, but also in informing us of potential issues with their individual datasets, how we can solve these problems, and for pointing us to other data sources we had not previously considered. The HERs are invaluable resources for understanding not only where sites and monuments are located, but where archaeological research has been conducted so that we can better understand the patterns in data we are beginning to see.

One of the key aspects of our project is investigating regional differences in the burial evidence from AD c. 300-800 by comparing sites and monuments data recorded at Historic Environment Record (HER) offices and through investigating published and unpublished site reports. We have spent most of our time up to this point building our database of sites; with Sue focusing on a bespoke Access database detailing every individual grave in Northumbria based on archival research while Brian has built the GIS geodatabase of funerary sites and their spatial locations. As we are building distinct databases that will later be merged for analysis, we have encountered different problems with the types of data we are gathering and thought it would make an interesting post to look at some of the challenges we are encountering.

HER Data

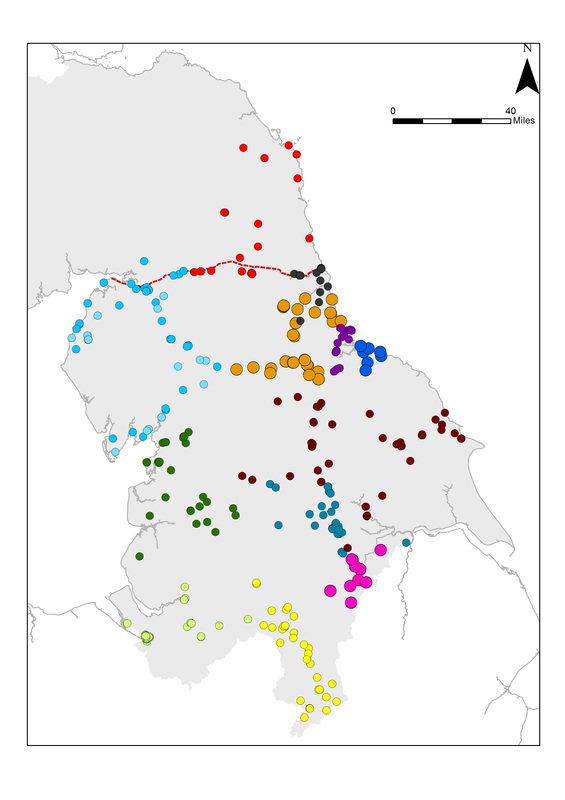

Thus far we have obtained sites and monuments data from almost all of the English HERs in our study region, and are actively acquiring the remaining English data now (Figure 1). The next step in data collection is contacting the Scottish HERs over the next few months in order to build up our GIS database of sites. Many thanks are necessary to these HERs for their assistance in not only supplying the data, but also in informing us of potential issues with their individual datasets, how we can solve these problems, and for pointing us to other data sources we had not previously considered. The HERs are invaluable resources for understanding not only where sites and monuments are located, but where archaeological research has been conducted so that we can better understand the patterns in data we are beginning to see.

Figure 1: Site data obtained from Historic Environment Record Offices as of January 2016

One issue with working with the site databases is that each HER has distinct protocols for identifying and recording archaeological sites and monuments. These conventions include different criteria on what constitutes a site, how/why and when are temporal periods assigned to these records, what is the format of the HER database, how sites are labelled, .etc. These differing practices affect the types and amounts of data we have received and as such we have made our queries to the HERs as broad as possible in order to capture all relevant site and monument records related to late-Roman and Early Medieval burials in Northumbria.

Multi-period sites are a good example of how these different conventions affect the data we receive from the HERs. For example, one HER could record a cemetery that has prehistoric and early medieval burials as one site while another HER would record the same cemetery as two different sites. This obviously alters the results of spatial analysis and density patterns associated with this cemetery depending on if it is one or two sites. In order to address this, good communication with each HER office is essential to understand the datasets and how they were constructed. All of the HERs we have been in contact with have described their data to us in detail and have shed light on how these databases were constructed. Secondly, Brian will be building a bespoke GIS geodatabase. The site data from the HERs will be collated and inputted into this geodatabase one at a time so that any of the above issues will be settled upon at an individual site basis. Currently the plan is to assign an individual site ID number for each cemetery, not each time period. Each site will have attributes related to the various phases, artefacts, monuments, etc. that can then be used to query and perform spatial analysis. By creating our own geodatabase, the entirety of our study region will have all the sites in one format, enabling broad cross-regional comparisons.

Troublesome fiches

The digital age we’re now in allows us to accumulate vast amounts of data – but what if you can’t find the data because the microfiche fell out of the back of the monograph?

What went on to microfiches and how was it decided? Apparently the raw data of bone reports, technical analyses and sometimes whole grave catalogues, so that the publication text can focus on the discussion of the artefacts and the wider context - the fiches with the Castledyke South, Barton on Humber cemetery excavation report are hanging on precariously by a paper clip – as purchased. But, these interpretations can change and we need to test ideas against the raw data. The Early Anglo-Saxon Census, now being extended into Northumbria through the People and Place Project, requires base-line data and omits the discussion – the purpose being to provide census type records for each individual. Currently, the situation is variable – some sites have their microfiche data brought into the public domain, particularly if associated with major sites: for example CBA research reports available on-line have the microfiche contents included, but other more locally produced publications may not receive the same treatment – a case in point is Sewerby, East Yorkshire (Hirst 1985, York University Archaeological Publications 4) – some new copies complete with microfiche are still available for purchase – the well-thumbed UCL Institute of Archaeology copy has long since lost its fiche from the back pocket. Once a copy complete with fiche was obtained the next problem was to read it – microfiche readers are rare items and they do not have the facility for printing off copies that can be annotated into a database. Evidently there is a method of scanning fiches and fiddling with them in Photoshop to produce A4 copies, but this is tricky and tedious for several hundred pages of text. Fortunately, Sue Hirst, the author of the Sewerby volume, was able to supply a paper copy of the original text. Less luck is being had with the microfiche from Chris Loveluck’s 1994 doctoral thesis. All the data for the East Yorkshire sites – including the still unpublished Garton Station cemetery – is in volume 3 – submitted on microfiche. Durham University did not digitise volume 3 – perhaps it too had fallen out of the back of volume 2 or they didn’t have the means to reproduce it. This leads me to wonder about changing attitudes to data – was information consigned to a fiche because it was perceived that no one other than the truly dedicated would wish to read it. Perhaps publication costs precluded the full presentation of the report. Are things any better now or have the fiches been replaced with CD-Roms, but still held in a pocket inside the back cover? What data was lost on these flimsy plastic sheets or can it be retrieved for curation into the digital age?

One issue with working with the site databases is that each HER has distinct protocols for identifying and recording archaeological sites and monuments. These conventions include different criteria on what constitutes a site, how/why and when are temporal periods assigned to these records, what is the format of the HER database, how sites are labelled, .etc. These differing practices affect the types and amounts of data we have received and as such we have made our queries to the HERs as broad as possible in order to capture all relevant site and monument records related to late-Roman and Early Medieval burials in Northumbria.

Multi-period sites are a good example of how these different conventions affect the data we receive from the HERs. For example, one HER could record a cemetery that has prehistoric and early medieval burials as one site while another HER would record the same cemetery as two different sites. This obviously alters the results of spatial analysis and density patterns associated with this cemetery depending on if it is one or two sites. In order to address this, good communication with each HER office is essential to understand the datasets and how they were constructed. All of the HERs we have been in contact with have described their data to us in detail and have shed light on how these databases were constructed. Secondly, Brian will be building a bespoke GIS geodatabase. The site data from the HERs will be collated and inputted into this geodatabase one at a time so that any of the above issues will be settled upon at an individual site basis. Currently the plan is to assign an individual site ID number for each cemetery, not each time period. Each site will have attributes related to the various phases, artefacts, monuments, etc. that can then be used to query and perform spatial analysis. By creating our own geodatabase, the entirety of our study region will have all the sites in one format, enabling broad cross-regional comparisons.

Troublesome fiches

The digital age we’re now in allows us to accumulate vast amounts of data – but what if you can’t find the data because the microfiche fell out of the back of the monograph?

What went on to microfiches and how was it decided? Apparently the raw data of bone reports, technical analyses and sometimes whole grave catalogues, so that the publication text can focus on the discussion of the artefacts and the wider context - the fiches with the Castledyke South, Barton on Humber cemetery excavation report are hanging on precariously by a paper clip – as purchased. But, these interpretations can change and we need to test ideas against the raw data. The Early Anglo-Saxon Census, now being extended into Northumbria through the People and Place Project, requires base-line data and omits the discussion – the purpose being to provide census type records for each individual. Currently, the situation is variable – some sites have their microfiche data brought into the public domain, particularly if associated with major sites: for example CBA research reports available on-line have the microfiche contents included, but other more locally produced publications may not receive the same treatment – a case in point is Sewerby, East Yorkshire (Hirst 1985, York University Archaeological Publications 4) – some new copies complete with microfiche are still available for purchase – the well-thumbed UCL Institute of Archaeology copy has long since lost its fiche from the back pocket. Once a copy complete with fiche was obtained the next problem was to read it – microfiche readers are rare items and they do not have the facility for printing off copies that can be annotated into a database. Evidently there is a method of scanning fiches and fiddling with them in Photoshop to produce A4 copies, but this is tricky and tedious for several hundred pages of text. Fortunately, Sue Hirst, the author of the Sewerby volume, was able to supply a paper copy of the original text. Less luck is being had with the microfiche from Chris Loveluck’s 1994 doctoral thesis. All the data for the East Yorkshire sites – including the still unpublished Garton Station cemetery – is in volume 3 – submitted on microfiche. Durham University did not digitise volume 3 – perhaps it too had fallen out of the back of volume 2 or they didn’t have the means to reproduce it. This leads me to wonder about changing attitudes to data – was information consigned to a fiche because it was perceived that no one other than the truly dedicated would wish to read it. Perhaps publication costs precluded the full presentation of the report. Are things any better now or have the fiches been replaced with CD-Roms, but still held in a pocket inside the back cover? What data was lost on these flimsy plastic sheets or can it be retrieved for curation into the digital age?

RSS Feed

RSS Feed