|

P&P had a substantial representation at this year’s conference, held in the beautiful Aula Magna auditorium of Stockholm University. Our four posters, and those of Durham colleagues Celia Orsini and Sian Mui, garnered many interested comments and expectations for the outcomes of the project. The field trip to Runsa hilltop settlement, Gamla Uppsala with its monumental burial mounds – a visit enlivened by lunch from a Mexican snack wagon (well done to the organising committee for dreaming up that one!) – and Valsgärde with its collection of cremations, chamber graves and boat burials, together with a stone ship setting, made for an extraordinary day, ending in a welcome drinks reception at Uppsala Castle. Key themes from the conference presentations that struck us as particularly relevant to the project were European-wide incidences and analyses of disease, such as plague and the evidence for climate change. We all came away using the handy acronym LALIA – the Late Antiquity Little Ice Age of the sixth century AD. My highlights? The virtual reality app recreating the great hall building at Gamla Uppsala and a first ever sighting of a white-tailed eagle, floating timelessly above the fjord. Stuart Brookes discussing a poster with Charlotte Behr and Leslie Webster (photo courtesy of Chris Scull) The Gamla Uppsala great hall on the virtual reality app (photo: Sue Harrington) The burial site of Valsgärde (photo: Sue Harrington)

0 Comments

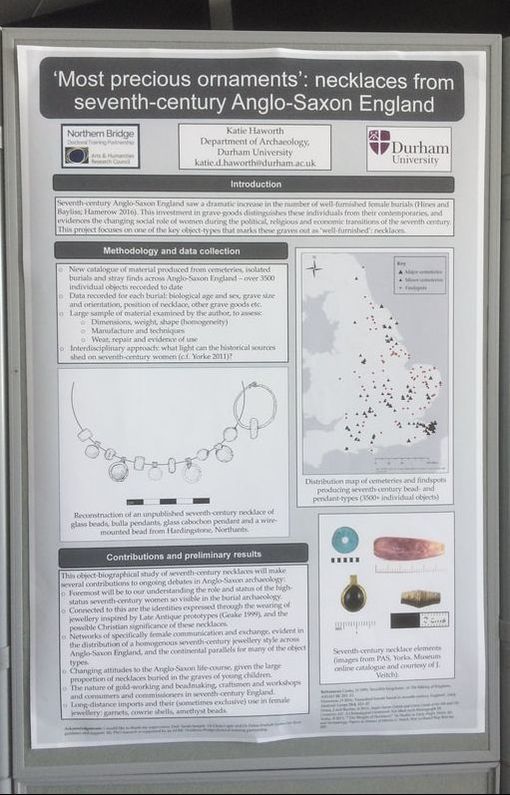

SMA Annual Conference report: Grave Concerns: Death, Landscape and Locality in Medieval Society12/10/2018 This year’s Society for Medieval Archaeology annual conference took place at Durham University across the 13th to 15th of July, 2018. The conference, a collaboration between the Society and a Leverhulme-funded project hosted at Durham called People and Place: Creating the Kingdom of Northumbria, addressed the topic of death and burial in early to late medieval Britain and Europe. Since 1990 a series of major conferences and publications have investigated aspects of death and burial in medieval societies in Europe and beyond. Some have delivered state-of-the-art research on early medieval and medieval funerary rites; others have profiled new advances in scientific research. The proceedings of the last SMA conference that dealt with burial were of course published in 2002 in the Society monograph series by Sam Lucy and Andrew Reynolds in the seminal volume Burial in Early Medieval England and Wales, which captured some of the major changes in thinking at the time on identity, community and belief. Since then spatial consideration has developed as a significant research strand in medieval archaeology, relevant to understanding settlement patterns, land use and travel and the experiential nature of monuments, places and landscapes. From exploring the distribution patterns of grave types and the use of antecedent landscape features for burial and charting the rise of commemorative markers in stone, to identifying patterns of diseases and health in medieval populations and their mobility; the location of the grave has become a rich stepping off point, stimulating and facilitating new research directions. The delegates convene for the opening keynote lecture by Professor Bonnie Effros (University of Liverpool) 'New eyes on ancient cemeteries? Merovingian mortuary archaeology in the age of Inrap' With this in mind, the 2018 conference brought together established and early career researchers working on aspects of death, landscape and locality from AD 300-1500 in Britain and Europe. A key concern of the event was to promote new dialogues bridging early medieval, medieval and late medieval funerary archaeology and to initiate a broader transnational and comparative debate on methods, theories and approaches relevant to mortuary archaeology in the Middle Ages. The content delivered by our 21 speakers did not disappoint and it was particularly pleasing to listen to wide-ranging sessions that juxtaposed perspectives from Dalmatia and Pictland, or the Low Countries and Ireland, mixed scientific and social approaches and dissolved chronological divisions. We were fortunate in having three exceptional and thought-provoking keynote papers. We started with a review of the treatment and exploration of Merovingian mortuary archaeology in past and present from Bonnie Effros on Friday evening in Durham Cathedral. Despite the imposing venue of the Cathedral Chapter House, our speaker kept the audience fully engaged in a critical reflection on the relevance of considering mortuary archaeology in context and a reception followed in the late evening light in the medieval cloister. On Saturday evening the audience heard an inspiring exploration of experiential and individual approaches to understanding human interactions with death in the medieval era from Roberta Gilchrist followed by another sunshine-filled reception at the poster evening in the Calman Centre with views over the historic Durham peninsular. Finally we closed on Sunday with a rich exploration of the architecture and grammar of mortuary archaeology in early Anglo-Saxon England from Duncan Sayer, leaving the audience with considerable food for thought on their journey home. In between our speakers provided new insights into cremation in Britain and the near Continent; explored the rich evidence for monument reuse in Scotland, Dalmatia and Francia; and charted the experiential nature of sculpture, burial and travel as elements of Norse tradition and in the context of Irish and western Christianity. Papers highlighted some recent seminal cemetery excavations such as Vicq in France and Lakenheath in Suffolk, while other speakers drew on the material evidence of the grave contents to explore aspects of ritual practice such as the use of gold coins, or the bioarchaeological contribution of skeletal assemblages. Important themes to emerge included the intersection of domestic and funerary spheres, the idea of resilient traditions during times of change, the importance of experiential approaches to graves, cemeteries and funerary landscapes and the need to individualise and anthropologise death and understand medieval experience. Professor Roberta Gilchrist (University of Reading) delivering one of the keynote lectures 'Unleashing Heterodoxy: An anthropological agenda for later medieval burial archaeology' We were also fortunate in receiving a broad range of poster presentations. Some 20 posters were covered research topics including funerary practice in Normandy, the fifth-century Thames Valley, bioarchaeological perspectives on Anglo-Saxon bed burials, life and death in Ipswich, and micromorphological exploration of the Pictish grave fills at Rhynie, in Aberdeenshire, Scotland. The Society awarded prizes to two researchers for their posters on Riia M. Chmielowski for Viking-Age steatite: do household objects reveal real differences in status? And Celia Orsini for Monument reuse: localised identity, regional diversity and a poster by Elizabeth O’Brien and her team on the Mapping Death project in Ireland: People, Boundaries and Territories in Ireland, 1st to the 8th centuries AD was highly commended by the judges. Poster by Katie Haworth (Durham University) "'Most precious ornaments': necklaces from seventh-century Anglo-Saxon England" Thus in a friendly setting, the conference delivered state-of-the-art research and outlined new agendas in the field of medieval funerary rites. It also gave a voice to a range of new early career researchers alongside more established academics, providing attendees with a privileged insight into the up-and-coming new work that will no doubt change how we think about and use burial and cemetery evidence in medieval research in the decade to come.

Sarah Semple, Celia Orsini and Kate Mees, Durham University, UK Since 1990, a series of major conferences and publications have investigated aspects of death and burial in medieval societies in Europe and beyond. Some have delivered state-of-the-art research on early medieval and medieval funerary rites; others have profiled new advances in scientific research. Throughout all, spatial consideration has emerged as a connecting research strand.

From understanding the distribution patterns of grave types and the use of antecedent landscape features for burial, to charting the rise of commemorative markers in stone, and the arrival of monastic and churchyard burial traditions; from exploring political signalling and polity formation through burial display, to identifying patterns of diseases and health in medieval populations and their mobility, the location of the grave has become a rich stepping off point, stimulating and facilitating new research directions. This conference, sponsored by the Society for Medieval Archaeology and the Leverhulme-funded Durham Project People and Place: Creating the Kingdom of Northumbria, brings together established and early career researchers working on aspects of death, dying and burial from AD 300-1500 in Britain, Ireland and further afield. The conference will take place at Durham University and opens on the evening of Friday the 13th of July at Durham Cathedral, with a keynote lecture by Professor Bonnie Effros (University of Liverpool). A free private view of the new Open Treasure exhibition at the Cathedral will be available to full ticket attendees and a drinks reception will follow the evening lecture. On the 14th and 15th of July, speakers from Britain and Europe will present new work and findings on death and burial in medieval society at the Calman Centre on the Science Site at Durham University, and a second keynote will be given on Saturday evening by Professor Roberta Gilchrist (University of Reading), followed by an evening reception and poster exhibition. The conference will close on Sunday the 15th of July with a final keynote by Dr Duncan Sayer (University of Central Lancashire). Speakers include: Mary Lewis (University of Reading), John Hines (Cardiff University), Jean Soulat (LandArc Laboratory and CNRS Research Unit UMR 6273 from CRAHAM), Adrian Maldonado (University of Glasgow), Ann Sølvia Jacobsen (Durham University), James Graham Campbell (UCL), Dries Tys (Free University of Brussels), Jure Šućur (University of Zadar), Anouk Busset (University of Glasgow) and Catriona McKenzie (University of Exeter). See the full provisional programme here Registration and Fees To register for the conference please complete the registration form available here (as a word document and editable .pdf) and email it to [email protected]. Payment can be made by cheque to ‘Durham University’ and the cheque should be sent to Prof Sarah Semple, Department of Archaeology, Durham University, South Road, Durham, DH1 3LE. We can also take online payments and payments by international bank transfer, please indicate when registering if you need to pay by either of these methods and we will provide you with the account details by email. For all queries please contact us at [email protected] (phone on 0191 334 1115). Conference Fees Full attendance: £95 This includes access to the full programme and all keynote lectures, a free private view of Open Treasure, attendance at both evening receptions, lunch on the Saturday and all refreshments at the conference on Saturday and Sunday. Basic attendance: £80 This includes access to the full programme and all keynote lectures. The following are NOT included: private view of Open Treasure, the evening receptions, lunch on Saturday and refreshments at the conference on Saturday and Sunday. Society for Medieval Archaeology Members’ Rate: £30 We are delighted to offer full attendance at the entire conference to all members of the Society for Medieval Archaeology for a special rate of £30. This includes access to the full programme and all keynote lectures, a free private view of Open Treasure, attendance at both evening receptions, lunch on the Saturday and all refreshments at the conference on Saturday and Sunday. The Society aims to offer as many free events to members as possible, in light of the opportunities for members to access a private view of Durham Cathedral’s new exhibition, attend two evening receptions and a poster exhibition, there is a basic charge which contributes to the running and staffing costs associated with these events. Attendance of the main programme, the keynote lectures, the refreshments and lunch on Saturday are all included in this basic price for members. TO JOIN THE SOCIETY PLEASE VISIT THE FOLLOWING PAGE: http://www.tandfonline.com/pricing/journal/ymed A full or family membership is £35, membership for retirees is £28 and student membership is £20. Dr Stuart Brookes joins the People and Place team on 1 November. Stuart specialises in comparative landscape studies in early medieval Europe, and will be taking over the role of spatial analysist from Brian Buchanan who is leaving to take up an Assistant Professorship at Eastern Washington University at the end of the year. Stuart’s recent work has concentrated on the landscape archaeology of Anglo-Saxon civil defence, the structure of governance and administration in early medieval states, and travel and communication in Anglo-Saxon England, published as Beyond the Burghal Hidage: civil defence in Anglo-Saxon England (with John Baker, 2013), Landscapes of Defence in the Viking Age (with J. Baker and A. Reynolds, 2013), Travel and Communication in Anglo-Saxon England (in prep). He is looking forward to working closely with the team as it enters the next exciting stage.

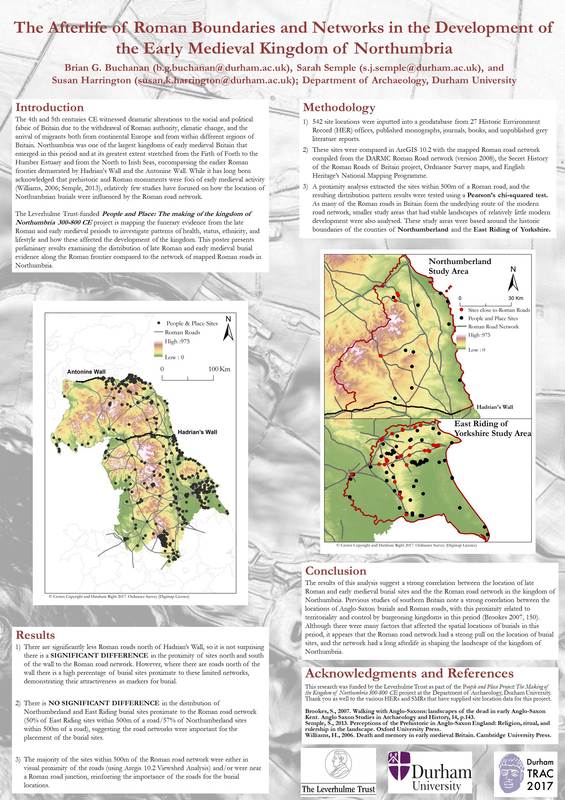

People and Place is charting the entirety of the burial record for the kingdom of Northumbria at its greatest possible extent. We are two years in to our project and have now reached the final stages of data collection. Our database records all archaeologically attested early medieval burials within the kingdom at its largest extent currently includes approximately 550 sites and +3000 individuals. The sites, individuals, and associated artefacts are all logged within our access database, allowing us to spatially map relationships between these sites and the natural and human altered landscape, within localities and across regions. Aerial photograph of excavations of Binchester cemtery. 2017, © David Petts This month we are releasing a pilot sample and we’d like your opinion on how accessible this data is, how usable and how we might improve our online delivery. We’ve chosen to offer you our mortuary data from the County of Durham. This blog will take you via this link to a new page on our website: County Durham Data. Here users will find three tables presented as .pdfs – these list the sites, the individual burials from these sites and the artefacts that were recovered with those burials. Three information sheets are also present to help users navigate the lists and use them to identify information about locations, individual graves and artefacts. We have also produced sample maps: a basic plot of sites, the sites mapped in relation to elevation, to rivers and to Roman roads. So please ‘dig in’! We are very keen to receive feedback on the usability so we can shape our ultimate release of all data online. We’d like to hear your views before the 1st of December 2017. Please send all your comments to Brian at [email protected].The People and Place team recently presented a poster at TRAC 2017. The 27th annual Theoretical Roman Archaeology Conference (TRAC) was hosted by the Department of Archaeology and the Department of Classics and Ancient History at Durham University from the 28th to 31st of March, 2017. TRAC is a multidisciplinary symposium focused on theoretical approaches to Roman studies, and is one of the largest gatherings of Roman scholars in the world. The People and Place team presented a poster entitled ‘The Afterlife of Roman Boundaries and Networks in the Development of the Early Medieval Kingdom of Northumbria.’ The poster presented at TRAC 2017 examined the distribution of late Roman and early medieval burial evidence from our database and compared this to the network of mapped Roman roads in Northumbria. While it has long been acknowledged that prehistoric and Roman monuments were foci of early medieval activity, relatively few studies have focused on how the locations of burials within the boundaries of the kingdom of Northumbria were influenced by the Roman road network.

The 542 site locations currently in the People and Place database were analysed using ArcGIS 10.2. The sites were compared to a Roman road network mapped from combining the results of DARMC Roman Road network project (version 2008), the Secret History of the Roman Roads of Britain project, Ordnance Survey maps, and English Heritage’s National Mapping Programme. A proximity analysis extracted the burial sites within 500m of a Roman road, and the resulting distribution pattern results were tested using a Pearson’s chi-squared test. As many of the Roman roads in Britain form the underlying modern road network, smaller study areas containing stable landscapes of relatively little modern development were also investigated using the historic boundaries of Northumberland and the East Riding of Yorkshire. The results demonstrate a significant difference in the proximity of burial sites north and south of Hadrian’s Wall in comparison to the Roman road network, with the sites south of the wall in general positioned closer to the road network. This is perhaps not surprising as there are significantly less Roman roads north of the wall. However, where there are roads north of the wall, there is a high percentage of burial sites proximate to these limited networks, demonstrating their attractiveness as markers for burial. This was further supported in the analysis of the smaller study areas which demonstrated no significant differences in the distribution of Northumberland and East Riding burial sites proximate to Roman road networks. Finally, the majority of the sites within 500m of the Roman road network were in visual proximity of the roads based off of a viewshed analysis using the 5m digital terrain model of the project area. The results of this analysis, while preliminary, suggest a strong correlation between the location of late Roman and early medieval burial sites and the Roman road network in the kingdom of Northumbria – something we plan to investigate further. The People and Place project has completed our identification of burial sites in Northumbria and have a very detailed list of over 550 locations in the database. We are now moving in to the second phases of our investigations and this includes the weighing of grave goods from around the region. Obviously finding over 6000 objects in museum archives would be an unrealistic undertaking, so we have adopted a sampling strategy based on easily accessible material with good publication. To that end some of the team spent the day (April 27, 2017) in the stores of Tees Archaeology in Hartlepool (http://www.teesarchaeology.com/home/home.html), recording metalwork from the Mill Lane mixed rite cemetery from Norton, published by Steve Sherlock and the late Martin Welch in a CBA volume in 1992 (available on line). Many of the higher status and more immediately attractive artefacts are on display in Preston Park Museum, Stockton-on-Tees, but this is not a problem in terms of the weighing methodology. What the methodology seeks to achieve is an interpretation of the background ‘noise’ of the use of raw materials in the more everyday objects by different inhuming communities. Only complete metal artefacts were weighed in a Fordist regime of unpacking, inspecting, weighing, recording and repacking – a surprisingly swift and efficient routine. In a list a knife is just a knife, perhaps with a typology applied based on shape. By weighing we can record in shorthand the differences between objects of the same type and by accumulating data interpret these differences over time and space. Already today we could demonstrate that most knives from Norton were rather insubstantial, even the Evison Type 1 knives, probably the most common form nationally, particularly in comparison to those from iron-rich communities in the south east of England. Even this seax is not as weighty as its southern counterparts. The very commonly found annular brooches vary in weight from 3g to 12g, but this data helps us to reflect on the varying forms found in the burials, with small but dense objects outweighing their larger but flatter counterparts. Unusually there are iron annular brooches here too and they are generally heavier – a usage of raw material that sits in contrast to the perception, from the knives, of the Norton community as being iron poor. There are more substantial copper alloy objects deployed in the burial, such as florid cruciform brooches, but of particular interest will be the long dress pins that on current data appear to be more uniform in weight across different sites in the study region.

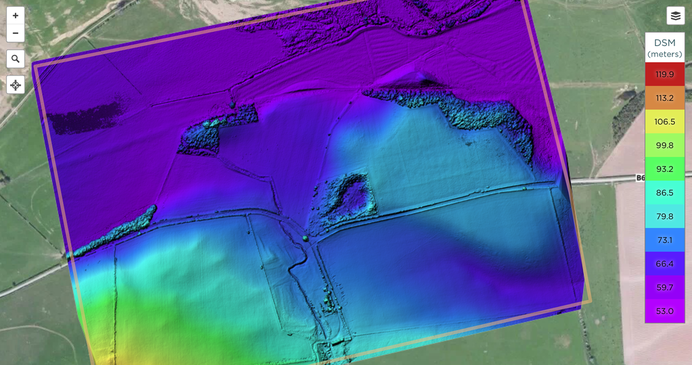

Our thanks go to Rachel Grahame for allowing us access to the archive. Our visit to Hartlepool concluded with a trip over to the Headland, site of over 150 burials relevant to our project time frame, although with many more spread across this isolated and today a rather inhospitable location due to a heavy rain. At least we could catch up with Hartlepool’s most famous if mythical son Andy Capp! Sue Harrington I recently had the pleasure of accompanying a Durham University undergraduate, Darren Oliver, to the early medieval royal vill at Yeavering in order to conduct an aerial photographic survey of the site and its immediate environs. Darren is currently undertaking a systematic survey of the site for his undergraduate dissertation. He has constructed his own unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV), or drone, to take multi-spectral imagery of the landscape to determine if archaeological features are visible at different times of the year. Yeavering is located on a sand and gravel plateau overlooking the River Glen and in the shadow of Yeavering Bell along the northern limits of the Cheviot Hills. The royal palace complex of Yeavering, or Ad Gefrin, is discussed by Bede in his History of the English Church and People as the place where the missionary Paulinus accompanied the king and queen of Northumbria in AD 627 to instruct and baptize the local populace (HE II, 14). Yeavering was identified by aerial reconnaissance in 1949 (Knowles and St Joseph 1952, 270-1) and was excavated throughout the 1950s and 60s by Dr Brian Hope-Taylor (Hope-Taylor 1977). These landmark excavations revealed multiple phases of settlement from the early medieval period, and are considered a seminal moment in British field archaeology due to the methods used by Hope-Taylor and the fact that Yeavering is a type-site for understanding early medieval palace complexes. It is an important site for the People and Place project, as numerous burials were excavated by Hope-Taylor, and were assigned to pre- and post-Christian contexts. As such I was interested in learning more about UAV flights and their potential in revealing early medieval burials and cemeteries. UAV ready to fly, resting within the boundary's of the site. The use of aerial drones to survey the archaeological landscape is a burgeoning technique in archaeological investigation, recording, and analysis. Aerial photography has a long and important history in the archaeology of Britain, as attested to by the discovery of Yeavering and other sites in Northumberland through cropmarks, parchmarks, and soilmarks. One of the primary down-sides of traditional aerial photography is the cost and training required to either commission flights or to undertake the training to be a pilot. The growth in UAVs over the last decade has provided a more affordable way to conduct aerial surveys, and has only recently been incorporated into archaeological methods and practice. Darren’s work at Yeavering is concentrating on examining the archaeological landscape by focusing on taking photography outside the visual spectrum and investigating the reflectivity of the vegetation to identify archaeological features. He has conducted a systematic survey of the site by conducting flights every month throughout the year to determine if seasonal changes to vegetation and weather affect the visibility of archaeological features. Although additional burial evidence has not been identified through these surveys, new anomalies that are potentially related to the archaeological heritage of the site have been identified through his work at the site. Digital surface model of Yeavering and environs derived from photogrammetry of UAV imagery

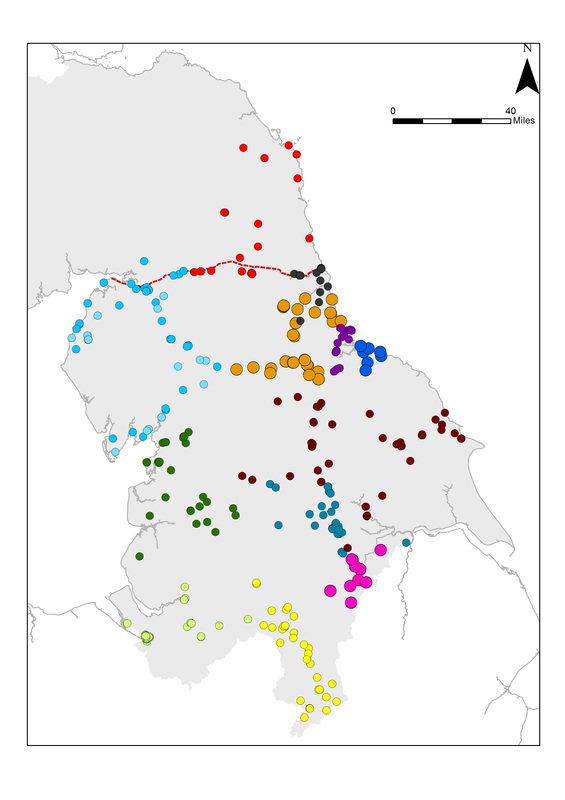

It was my first time seeing a UAV in action, and I was impressed at the abilities of the drone to survey the landscape both efficiently and quickly. As well as the ability to take high resolution RGB photos and multi-spectral images, drone photography can be used to model the topographic elevation of a landscape utilising photogrammetry. In addition, drones can be adapted to use LiDAR scanners in order to produce highly-detailed elevation models. Many thanks are necessary to Darren for demonstrating his drone and for his work at the site, which will be invaluable for understanding the archaeological environs of the site. Darren has taken drone flights at other archaeological sites in the region, and is keen to continue this work after his degree is finished at Durham for any other archaeologists working in Britain that would benefit from these techniques. You can see more of Darren’s work at: https://sketchfab.com/dojpot Knowles, David, and John Kenneth Sinclair St Joseph.Monastic sites from the air. University Press, 1952. Hope-Taylor, Brian. Yeavering, an Anglo-British centre of early Northumbria. HM Stationery Office., 1977. By Brian Buchanan and Sue Harrington One of the key aspects of our project is investigating regional differences in the burial evidence from AD c. 300-800 by comparing sites and monuments data recorded at Historic Environment Record (HER) offices and through investigating published and unpublished site reports. We have spent most of our time up to this point building our database of sites; with Sue focusing on a bespoke Access database detailing every individual grave in Northumbria based on archival research while Brian has built the GIS geodatabase of funerary sites and their spatial locations. As we are building distinct databases that will later be merged for analysis, we have encountered different problems with the types of data we are gathering and thought it would make an interesting post to look at some of the challenges we are encountering. HER Data Thus far we have obtained sites and monuments data from almost all of the English HERs in our study region, and are actively acquiring the remaining English data now (Figure 1). The next step in data collection is contacting the Scottish HERs over the next few months in order to build up our GIS database of sites. Many thanks are necessary to these HERs for their assistance in not only supplying the data, but also in informing us of potential issues with their individual datasets, how we can solve these problems, and for pointing us to other data sources we had not previously considered. The HERs are invaluable resources for understanding not only where sites and monuments are located, but where archaeological research has been conducted so that we can better understand the patterns in data we are beginning to see. Figure 1: Site data obtained from Historic Environment Record Offices as of January 2016

One issue with working with the site databases is that each HER has distinct protocols for identifying and recording archaeological sites and monuments. These conventions include different criteria on what constitutes a site, how/why and when are temporal periods assigned to these records, what is the format of the HER database, how sites are labelled, .etc. These differing practices affect the types and amounts of data we have received and as such we have made our queries to the HERs as broad as possible in order to capture all relevant site and monument records related to late-Roman and Early Medieval burials in Northumbria. Multi-period sites are a good example of how these different conventions affect the data we receive from the HERs. For example, one HER could record a cemetery that has prehistoric and early medieval burials as one site while another HER would record the same cemetery as two different sites. This obviously alters the results of spatial analysis and density patterns associated with this cemetery depending on if it is one or two sites. In order to address this, good communication with each HER office is essential to understand the datasets and how they were constructed. All of the HERs we have been in contact with have described their data to us in detail and have shed light on how these databases were constructed. Secondly, Brian will be building a bespoke GIS geodatabase. The site data from the HERs will be collated and inputted into this geodatabase one at a time so that any of the above issues will be settled upon at an individual site basis. Currently the plan is to assign an individual site ID number for each cemetery, not each time period. Each site will have attributes related to the various phases, artefacts, monuments, etc. that can then be used to query and perform spatial analysis. By creating our own geodatabase, the entirety of our study region will have all the sites in one format, enabling broad cross-regional comparisons. Troublesome fiches The digital age we’re now in allows us to accumulate vast amounts of data – but what if you can’t find the data because the microfiche fell out of the back of the monograph? What went on to microfiches and how was it decided? Apparently the raw data of bone reports, technical analyses and sometimes whole grave catalogues, so that the publication text can focus on the discussion of the artefacts and the wider context - the fiches with the Castledyke South, Barton on Humber cemetery excavation report are hanging on precariously by a paper clip – as purchased. But, these interpretations can change and we need to test ideas against the raw data. The Early Anglo-Saxon Census, now being extended into Northumbria through the People and Place Project, requires base-line data and omits the discussion – the purpose being to provide census type records for each individual. Currently, the situation is variable – some sites have their microfiche data brought into the public domain, particularly if associated with major sites: for example CBA research reports available on-line have the microfiche contents included, but other more locally produced publications may not receive the same treatment – a case in point is Sewerby, East Yorkshire (Hirst 1985, York University Archaeological Publications 4) – some new copies complete with microfiche are still available for purchase – the well-thumbed UCL Institute of Archaeology copy has long since lost its fiche from the back pocket. Once a copy complete with fiche was obtained the next problem was to read it – microfiche readers are rare items and they do not have the facility for printing off copies that can be annotated into a database. Evidently there is a method of scanning fiches and fiddling with them in Photoshop to produce A4 copies, but this is tricky and tedious for several hundred pages of text. Fortunately, Sue Hirst, the author of the Sewerby volume, was able to supply a paper copy of the original text. Less luck is being had with the microfiche from Chris Loveluck’s 1994 doctoral thesis. All the data for the East Yorkshire sites – including the still unpublished Garton Station cemetery – is in volume 3 – submitted on microfiche. Durham University did not digitise volume 3 – perhaps it too had fallen out of the back of volume 2 or they didn’t have the means to reproduce it. This leads me to wonder about changing attitudes to data – was information consigned to a fiche because it was perceived that no one other than the truly dedicated would wish to read it. Perhaps publication costs precluded the full presentation of the report. Are things any better now or have the fiches been replaced with CD-Roms, but still held in a pocket inside the back cover? What data was lost on these flimsy plastic sheets or can it be retrieved for curation into the digital age? The People and Place team recently undertook an initial scoping trip to assess the known locations of late Roman to early medieval burial and settlement sites in Northumberland. The purpose was to examine the location of each site in relation to the local environment and explore relationships with topography, water courses and sources and transportation routes. We were also checking locations to ensure we have precision data on cemetery locations. Several trends emerged on Day 1 which will of course see further analysis. For example, many of the sites we visited in northern Northumberland were located very close to water sources – notably either the coast or fairly prominent inland navigable rivers. The importance of water for transportation and as a natural resource is well recognised. The distribution of early medieval burial sites in relation to major inland water courses is a recognised feature of many areas of southern and eastern Britain. Bowl Hole Cemetery, Bamburgh, view to the east, with the North Sea beyond the dunes in background of image © Brian Buchanan. The Bowl Hole cemetery at Bamburgh, excavated by the Bamburgh Research Project team from 1998-2007 (https://bamburghresearchproject.wordpress.com), is located to the east of a small ridge within a bowl-shaped depression among extensive sand dunes on the North Sea coast. Much of the sand dune inundation is late in date. Never-the-less, we can assume that the cemetery flanking the early medieval elite complex, lay within close distance to the wild North Sea shoreline. In the Till valley or Milfield basin, river proximity is significant. Yeavering, excavated by Brian Hope-Taylor in the 1950s-60s, is situated on a gravel terrace adjacent to the River Glen. The settlement most likely dates to the 6th and 7th centuries AD. It was a villa regia, a royal centre containing large timber halls and two distinct burial areas. Other early medieval settlements in the Milfield Basin are located on similar gravel terraces overlooking the River Till and/or its tributaries. There appears to be a regional pattern of occupation and land use in the basin on gravel terraces immediately adjacent to rivers and river confluences and flood plains in the 6th-8th centuries AD. This pattern may also be related to archaeological visibility of early medieval cropmarks on these landforms but this does provide areas for future research. In contrast to the Milfield Basin where most of the known early medieval sites are located on the valley floors (albeit on elevated gravel terraces) the sites we visited in Coquetdale were along the valley’s edge on the top of the rolling hills leading down to the River Coquet basin. The situation of known Anglo-Saxon burial sites along the escarpment edge overlooking major river valleys offers evidence of apparently markedly different choices and motivations, much more familiar along the river valleys of Sussex and the eastern coast and East Yorkshire. . The sites we visited are largely findspots, although some have seen excavation, but casual discard or loss and other depositional processes need to be born in mind alongside settlements or cemeteries. Coquetdale, with the river Coquet at flooding level due to heavy rains © Brian Buchanan In addition we were interested in the relationship of Roman road networks and early medieval sites. The path of two Roman roads, the Devil’s Causeway and Dere Street lie in modern day Northumberland. A number of early medieval sites are located in close proximity to these roads. This project is also interested in understanding late-Roman burials in order to contrast their appearance, spatial location, and skeletal evidence with the early medieval sites. Our final stop on the second day was to Rochester, Northumberland to examine the relationship of Roman period burials to the Roman fort of Bremenium. The impressive ruins of the fort are at the confluence of Dere Street and a Roman road connecting this location to the Devil’s Causeway. The fort sits on the edge of a ridge overlooking the Rede valley. The fort was constructed during the Agricolan campaigns and was later rebuilt in the 2nd century AD. It remained a fortification even after the pullback to Hadrian’s Wall. The nearby burials, identified by the HER and placed in the late Roman period are within sight of the fort. The fort itself has extant walls and ditches and is well worth a visit! Early medieval metalwork finds have recently been discovered at Rochester suggesting that like many Roman sites in the North East, activity continued in the 5th-6th centuries AD. View of the southern Northumberland landscape, © Brian Buchanan We achieved a definite understanding and feeling for the landscape of Northumberland and the potential relationships and patterns in the locations of early medieval burials, settlements, and findspots. Perhaps most importantly we were able to reposition the sites in our GIS after visiting their locations. The regional differences in topographic relief, access to water, and geomorphology have begun to come into focus, and this trip provided a good example for field visits for the other parts of the study area.

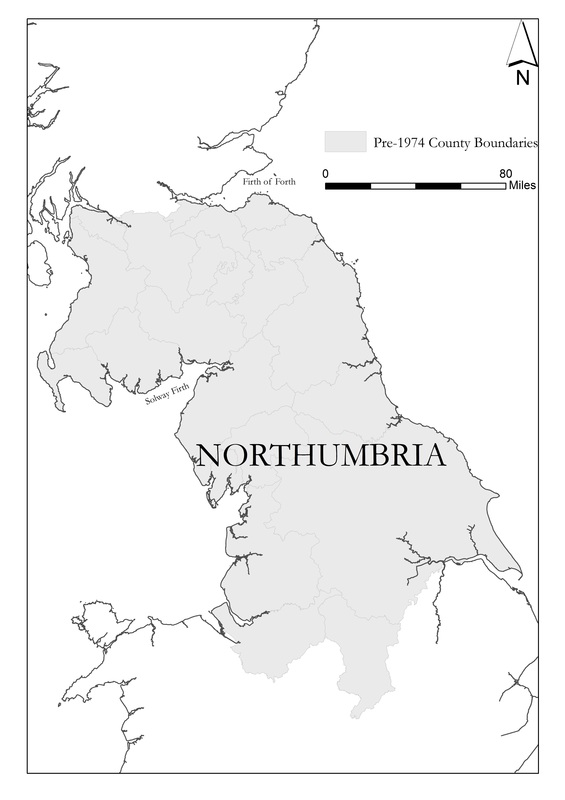

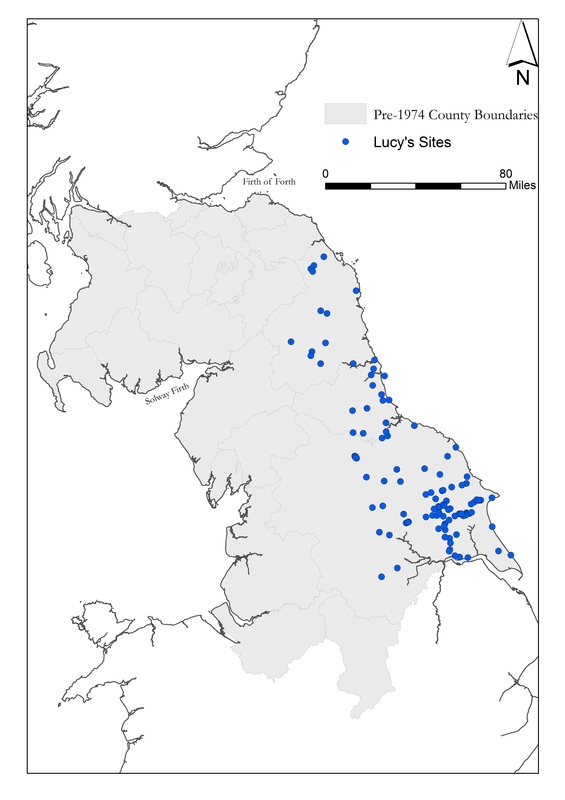

Welcome to the People and Place: The Making of the Kingdom of Northumbria 300-800 CE project blog. We will be using this space to update you on our project news and progress and upcoming publications. Our team of six researchers over the next three years will together undertake a major in-depth exploration of the full suite of burial evidence for the entire of the kingdom of Northumbria. Our project starts in AD 300, allowing us to capture information on burial rites and traditions in the century before the collapse of Roman military authority. We will chart and interrogate all burial evidence from this point to c AD 800, allowing investigation of the changing rites and traditions in their landscape context across a period of political, social and religious change. A major facet of the project is the integration of scientific applications – osteological and palaeopathological assessment of a large sample of skeletal remains, isotopic analyses and the applications of high resolution AMS dating. Today the blog is all about my work on the project. As a landscape archaeologist and GIS specialist, one of my primary tasks is the mapping of all known burials within the extent of the kingdom of Northumbria. One of the first steps has therefore been to define the spatial boundaries for the project. Northumbria’s boundaries were fluid, expanding or contracting according to conquests and losses. David Rollason notes the approximate boundaries of Northumbria at their greatest extent stretched from the North to Irish Sea and from the Cheshire and the Humber in the south to the Galloway and the Firth of Forth in the north (Rollason 2007, 2-7). Bede described in Historia Eccesiastica Gentis Anglorum in AD 731, that during King Edwin’s reign '[…] if a woman with a newborn child wanted to walk throughout the island from sea to sea she would meet no harm (HE II, 16, 191)', implying that Northumbrian royal control extended from the North to Irish Seas. While the coastlines offer a robust boundary for our study area to the east and the west, defining a cut off for the edges of the kingdom at its greatest extent to north and south is more difficult. At the outset therefore, the project is taking in data for England and Scotland from the following counties outlined below, purposely drawing in data from the broadest possible extent to reflect the fluid nature of the limits of this kingdom over time. Northumbria is noted for an imbalance in focus with much more research conducted on the eastern heartlands of the kingdom rather than the west (Clark 2011, 113). We hope to remedy this although a paucity of funerary data and issues of survival are well recognised challenges for the north west of England and the Scottish Borders. Our current working geographic extent can be seen here, boundaries are predicated on the pre-1974 boundaries for England and Scotland. Our scope allows us to include some assessment of the Peak District burials and bring in important burial data sets from the western Scottish borders. Building on past gazatteers and databases, such as those constructed by Sam Lucy (1998; 1999) and Helen Geake (1997), data is being drawn from regional research agendas, published handlists and catalogues and HeR and grey literature. The latter will require careful handling and detailed ‘cleaning’ to ensure we get the most productive and usable data sets possible for the initial GIS assessment. The project will include reassessment of graves and cemeteries in terms of form and location, the cataloguing of each individual burial facilitating a ‘census’ for the kingdom over time, re-visitation of all artefactual assemblages in terms of object type and date as well as scientific analyses of the remains of over 200 individuals. East Yorkshire will be used as a pilot study to test the database currently under construction by Dr Sue Harrington. This integrated relational database assigns unique values to individual burials along with information related to the depositional patterns, morphological characteristics and artefactual evidence of each grave. This is integrated into the GIS database I am designing in order to query spatial aspects of the data.

Clark, F 2011 'Thinking about Western Northumbria', in D Petts and S Turner (eds), Early Medieval Northumbria: Kingdoms and Communities, AD 450-1100. Brepols. Lucy, S 1999 'Changing burial rites in Northumbria AD 500–750', in J Hawkes and S Mills (eds), Northumbria's Golden Age. Sutton Publishing. Rollason, D 2007 'Northumbria: A failed European kingdom', in R Colls (ed), Northumbria: History and Identity, 547-2000. Phillamore Publishing. |

AuthorsDr Brian Buchanan, Dr Sue Harrington, Prof Sarah Semple, Dr Stuart Brookes Archives

February 2018

Categories |

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed